Post From Community Close Ups

The Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund II (HNEF II) is a novel financing approach demonstrating how intentional investments in a neighborhood’s built environment can be a powerful means to improve community health. The $42 million private equity fund provides patient, low-cost capital for the development of mixed-income , mixed-use real estate near transit sites in historically disinvested neighborhoods in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The fund’s underwriting process is unique: In addition to evaluating the financial risk of each development, it also screens for the project’s potential impact on community health. This innovative approach can help to spread and institutionalize an investment practice that prioritizes community well-being as much as financial incentives.

The Vital Conditions for Health and Well-Being by Well Being Trust, Community Initiatives and ReThink Health, provides a model for conceptualizing what drives holistic health and well-being. Build Healthy Places Network uses the Vital Conditions as a framework for describing the potential impact of the case studies we feature on health. This chart provides a snapshot of the ways HNEF II addresses each vital condition:

Everyone should have the opportunity to live in a thriving community that supports good health and environmental resilience. Yet, too many people in New England and across the country live in places where housing is unsafe, unhealthy and difficult to afford; healthy food choices are few; green space is limited; communities are disproportionately subject to climate impacts; and public transportation is inaccessible.

“Traditional models of investment tend to exclude low-income communities and reinforce the cycle of disinvestment, perpetuating disparities in health, wealth, and sustainability across generations,” said Virginia (Gina) Foote, Director of Impact Investment at the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF). “Health, housing, the environment, and the local economy are all deeply interconnected. We formed the Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund with the Massachusetts Housing Investment Corporation (MHIC) to solve these interrelated, complex issues in a more holistic, intentional way.”

K. Beth O’Donnell, MHIC’s Director of Community Investment, agrees. “Financing affordable housing and mixed-use real estate developments that strengthen community and environmental health is critical, particularly for under-resourced communities. HNEF II invests in developments that provide access to employment, healthy food, public transportation and walkable areas to revitalize neighborhoods, while simultaneously improving the health of residents.”

Bartlett Station, Building B, a $2.9 million HNEF I investment, completed in 2019

The creation of the Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund was spurred by a 2012 Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) study that identified gaps in financing for transit-oriented development in the Boston Metropolitan area. The area needed 76,000 new housing units to support 133,000 new jobs near transit by 2035, but was far from reaching this goal. The study revealed several roadblocks, including a lack of access to longer-term, less expensive capital for mixed-use, mixed-income developments in disinvested but emerging communities. Finding a solution to this barrier became the impetus for the creation of the Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund I (HNEF I), the first iteration of the fund.

HNEF I raised over $22 million and invested in nine developments that created 586 new units of mixed-income housing, 48,323 square feet of commercial space, and more than 110 permanent jobs in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods across the Boston Metropolitan area. It also became the blueprint and proof of concept for Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund II (HNEF II), which currently includes investments in mixed-use real estate developments in Brockton, Dorchester, Roxbury, and Hamilton, Massachusetts, with more to come across Greater Boston.

“Traditional models of investment tend to exclude low-income communities and reinforce the cycle of disinvestment, perpetuating disparities in health, wealth, and sustainability across generations.”

Like HNEF I, HNEF II is managed by Massachusetts Housing Investment Corporation and Conservation Law Foundation. However, a distinct difference between the first version of the fund and the second is a simplified structure.

HNEF I included three Classes of investors with different rates of return and levels of risk (see diagram). Class B and C investors made up nearly a third of HNEF I’s capital, and included program related investments and guarantees from foundations, such as Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, the Boston Foundation, state funds, and CDFI grants from the Federal Treasury. These ‘first loss’ investors had greater flexibility around requiring a return on their investment. Class A investors, which included banks and healthcare systems, required greater certainty on their returns. These investors were placed in a lower risk category of loss and backed by the Class B and C investors.

Image: HNEF 1 Structure

In 2013, when MHIC and CLF began fundraising, the composition of the fund proved to be important. Many banks and other investors were still nervous about the financial crisis and hesitated to invest in a new, cutting-edge private equity fund. Conversely, K. Beth O’Donnell, Director of Community Investment at MHIC, noted that while fundraising from foundations can be challenging, these organizations are “more interested in using their funds for proof of concept, and then, once that concept is successful, they want market forces to make it work.”

By the time HNEF II went to market, it used the success of HNEF I to attract more Class A type investors. This approach allowed the fund managers to experiment with a simplified structure that consisted of only one Class of investors, limited partners. In this simplified structure, MHIC and CLF, invest the ‘first loss’ capital that makes up 5% of the overall investment. This mitigates risk for all the other limited partners, who provide investments without input into the management of the fund. This time around, much less subsidy is required to attract HNEF II investors. Subsequently MHIC and CLF have raised over $40 million in investments, almost double the size of the original fund.

One of the most salient innovations pioneered by HNEF I is the use of the HealthScore. This tool screens investments, using both qualitative and quantitative data, to evaluate whether they have the potential to improve health for the community.

The HealthScore screening tool is informed by the Healthy Neighborhood Study (HNS), a participatory action research project that explores how neighborhood changes, such as new real estate developments, impact the health of residents. With a focus on residents’ lived experience, community members are involved in the survey design, data collection and analysis, and the HNS team also supports community-led actions informed by the findings.

Informed by the HNS, the HealthScore is designed to make a holistic assessment of an investment’s impacts. The framework both evaluates an investment’s contribution to strengthening the overall health of a neighborhood and assesses how the investment incorporates residents’ input and meets the community’s vision for equitable development.

The HealthScore aims to capture residents’ agency through metrics that evaluate how community vision and priorities are incorporated in the project and if the development process is inclusive of and responsive to community feedback.

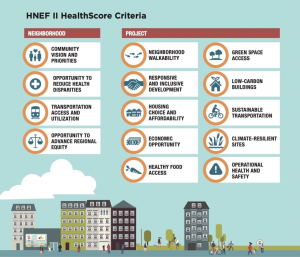

As co-sponsors of the fund, MHIC is charged with the financial underwriting and CLF leads impact assessment using HealthScore. The HealthScore is composed of:

The final recommendation for an HNEF investment is based on both the financial review and the total HealthScore for potential impact on community health.

The minimum HealthScore to be considered for investment is 50. Eligible HNEF developments receive a HealthScore rating of 50 to 100 based on a weighted average of the criteria below.

Image: HNEF II HealthScore Criteria

The scorecard is a model for how to measure and track the ways that real estate development can improve community health and sustainability by:

HNEF II uses a scoring process that includes a robust set of climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience criteria. Additionally, emerging research from HNS indicates that a sense of ownership over changes in one’s community is linked to higher levels of happiness as well as improved mental and physical health. The HealthScore aims to capture residents’ agency through metrics that evaluate how community vision and priorities are incorporated in the project and if the development process is inclusive of and responsive to community feedback. Please see a case study on 1463 Dorchester Avenue, an HNEF II investment, to learn how one developer incorporated a community’s vision and priorities throughout the development process.

In addition to screening projects for health impact, HNEF II investments also include HealthScore-related covenants in the investment documentation itself. These covenants add another layer of accountability that ensures developers deliver on their health and sustainability commitments. This feature and other aspects of HNEF II illustrate how a private equity fund can be designed to invest in new and equitable neighborhood developments that aim to bring lasting benefits to the health of residents and their communities.